Oh, if only life were simpler. If prices were easy to forecast, we could always buy low and sell high. And if falling demand always led to falling prices, or rising costs always led to rising prices, we’d know what to do all the time.

Unfortunately, the world is much more interesting than that. Our paper market has shown us that economists with a traditional knowledge of the industry can be as disoriented as the rest of us.

But there really is a logic to how the paper market moves. We all know it to be so. As individuals, we all have an idea of what is happening at any one point in time. We can feel the moment when a tight market changes and puts buyers back in control.

The problem is that we have difficulty foreseeing when it will happen more than a few weeks into the future. We just can’t seem to predict the future accurately. Frustrating.

There is a reason we can’t. There are too many things going on at the same time. They interact with one another and they move in nonlinear ways — meaning that a small change in supply or demand can sometimes produce a big move in prices. And at other times, a large change in supply or demand can have no effect whatsoever. Again, frustrating.

Technology to the rescue. The cost of manufacturing paper really does affect paper prices. Let’s look at how, and what this means in terms of reliably predicting paper prices.

Why prices are so hard to predict

Not only are there many interactive, nonlinear forces affecting the paper market, but prices of, say, rolls of paper are also affected by what happened at different parts of the supply chain at different times. For example, roll prices are affected by demand, but demand is affected by how much inventory merchants and printers have — as well as how much paper is actually being used for printing.

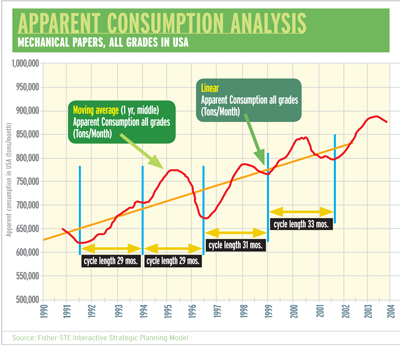

Today’s inventory levels, however, were determined by what merchants and printers did months ago. High prices at one part of the supply chain don’t necessarily translate to high prices at another part of the supply chain. The “Apparent Consumption Analysis” chart above shows that such effects can take months or years to play out.

It gets worse. Different forces affect prices differently at different times. Sometimes, for example, prices are affected by suppliers’ costs being high. When prices are already at the level of the cash cost of production, any further discount would cost the supplier real money for every ton sold.

Not many of us are willing to let that happen, so prices tend to stop falling when they reach the cash cost level of enough suppliers.

Even worse: As we’ve seen recently, cost-of-production levels can change quickly and dramatically when prices of fiber, energy and currency go up and down. We’ve felt energy and exchange rates rise and fall like a rollercoaster.

While this was going on, inventories and an unusual amount of substitution between different coated grades disguised the effect of changes in the end demand for printed products. As these changes worked their way up the supply chain, affecting inventory levels, mill operating rates, mill and machine closures and so on, costs were also changing. This caused prices to behave in what seemed like strange ways. People making those decisions were watching everyone else’s actions and adjusting their own decision-making accordingly. So what everyone was doing was affected by what everyone else was doing.

No wonder it’s so hard to predict paper prices. But it is possible.

Understanding a market’s dynamics

As we’ve seen already, the forces that make prices change are already operating in the supply chain. These forces are the result of rational decisions people have already made, given their own place in the supply chain, on factors such as capacity utilization, inventory, grade selections, order levels and capital investment.

Dealing with this complexity requires an understanding of the paper market’s forces and mathematics capable of handling the complexity. We have built models using the knowledge of industry professionals and a special kind of mathematics called system dynamics to explain the dynamics of paper markets for our clients since 1997.

So it’s possible to explain with a high degree of certainty that paper manufacturing costs do affect paper prices. We’ll use that model to explain what happened in 2007 and 2008.

What’s going on now? Seasoned paper experts seem split into two groups: Some insist that input costs drive paper prices, and others believe that they do not. Both are right — it just depends on what part of the cycle we are in.

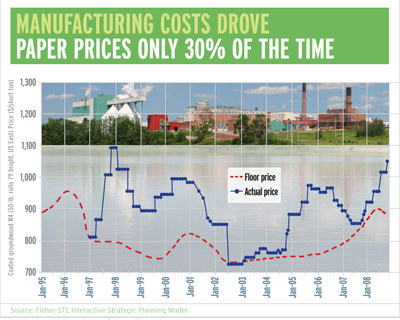

When the market has been soft long enough, paper prices tend to fall to the breakeven cost level of many producers. In such a case, input costs drive price movements. But when the price is above the breakeven costs, the cost of production has nothing to do with how prices are set: Costs can go up while prices come down or vice versa.

The rapidly rising costs of fiber and energy in 2007 started driving prices up. As people saw prices go up, they built inventory to guard against further price increases. Their buying for inventory drove prices even higher.

The cycle was perpetuated in part by the public believing that rising energy prices were the cause. They weren’t, but the old wives’ tale was revitalized. People are still trying to figure out why prices haven’t fallen as fast as costs appear to have fallen.

All markets have self-limiting cycles, and the paper industry hit one in late 2008. Buyers had built too much inventory and had started to ease off purchases. The moment arrived when control passed from sellers to buyers and prices started to fall.

Energy prices started falling more or less at the same time. Many people believed that lower costs should obligate paper producers to lower prices further.

But in this part of the cycle, producers were not at pure breakeven levels, so prices did not fall in lock-step with costs. Falling energy prices all by themselves just plain cannot cause paper prices to fall.

In fact, in the past 14 years, these costs have influenced price levels for coated freesheet and coated groundwood only 30% of the time. The rest of the time — when the floor has not been active — costs have had no impact on prices.

Continue on Page 2

The upside

It’s a good thing that costs don’t control prices. If they did, producers would always operate at breakeven. Shareholders and producers’ balance sheets would not be able to stand that, and producers would disappear. Producers make enough money at the tops of price cycles to maintain their equipment and balance sheets in the bottom half.

With an understanding of the market’s dynamics, you can plan for the ups and downs far enough ahead to budget accordingly. You can better negotiate contracts with the right length and terms. You can manage inventories to lower — or higher — levels more appropriately.

You can also time investments in capacity and M&A to maximize the use of precious capital. And, of course, you can hedge against cost increases and price swings.

Rodney Fisher ([email protected]) is president/founder of Fisher International, a consulting firm for pulp and paper manufacturing based in Norwalk, CT.