The world of direct response recognizes four Great Laws. The Laws apply to copy for all the media we use and misuse — direct mail, email and social media, print catalogs, online catalogs, telemarketing, point of sale, whispers into the ears of strangers.

All the Laws are so obvious we wonder, looking at the creative output of others, how anyone could bypass them. Yeah, right, because as we’re wondering about their copy, they are wondering about ours.

The First Great Law deals with reaching the most people who have the capability and potential desire to respond. The Third Great Law points out the loss of impact by failure to isolate the key selling argument and subordinating others. The Fourth Great Law emphasizes the benefit of imperative over declarative. Right now, we’ll center on the Second Great Law.

Why the Second? Because online versions of catalogs have propelled this Law into a negative prominence it seldom had before.

Heeding the Second Great Law

Explicitly, the Second Great Law is a warning to catalog and retail copywriters who express their frustration at being forced to run on tracks by over-“cleverizing” their output. The Law: In this Age of Skepticism, cleverness for the sake of cleverness may well be a liability rather than an asset.

Cleverness for the sake of salesmanship? Terrific. But cleverness just so the potential customer who chances upon your words will think, “What a clever person that copywriter is” — that’s improper, unprofessional and deadly. (Example — adding this to what I just wrote: “Improper, Unprofessional and Deadly, Attorneys at Law.”)

When a copywriter is too eager to show a chunk of copy to the rest of the staff, look out! That means the writer wants attention drawn to the writer, not to what’s being described.

One reason observing the Second Great Law will result in business saved is that clarity increases. And lack of clarity is the improper, unprofessional and deadly enemy of persuasion.

Look beyond the obvious

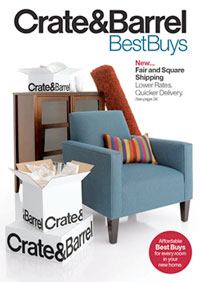

Here’s a well-respected catalog. The key wording on the cover: “New … Fair and Square Shipping.” Okay, what does this mean? Does “fair and square” mean some executive, hidden in a lofty tower, passes judgment on the charge for each shipment? Does it mean this company previously didn’t give its customers fair and square shipping? How does this compete against free shipping?

It’s a minor item, of course. But why have it as an item at all? (The explanation, on page 40, doesn’t help the salesworthiness of what’s intended to be a boost: “New … Fair & Square Shipping / No price charts. No math. No additional charges. Just our lowest Standard Delivery rates and our quickest shipping times ever … fair and square.”

And what have we learned from that? This: The copywriter was at the mercy of an idea he, she or it decided was clever. (Hey, creative department, ampersands increase the distance between seller and sellee. So replacing “and” with “&” on page 40 is a step sideways.)

Online, the home page of this cataloger reprises the pitch: “New … Fair & Square Shipping / No price charts. No math. No additional charges.” Then an invitation to click, “Learn more.” (“Learn” is almost always the most off-putting way to offer information.)

So we click. I don’t have enough space to report the windy and less-than-clear justification of “Fair & Square Shipping,” so you’ll have to take my word that it doesn’t generate an “I’m enthusiastic” reaction.

Sheesh! I started this column anticipating exposure of half a dozen pro or con examples of the Second Great Law. See how stated intentions and eventual outcome can be widely different?

Oh, well. If I’ve saved one catalog from pomposity, foolishness or obfuscation, I’ll rest easy. And if I haven’t, I’ll never know about it.

Herschell Gordon Lewis is the principal of Lewis Enterprises (www.herschellgordonlewis.com) in Pompano Beach, FL.