E-grocery sales were down both sequentially and year-over-year in January, driven mostly by declines in the ship-to-home category, but gains from pre-pandemic levels have mostly held even though delivery options have been impacted by inflation, according to a Brick Meets Click/Mercatus report.

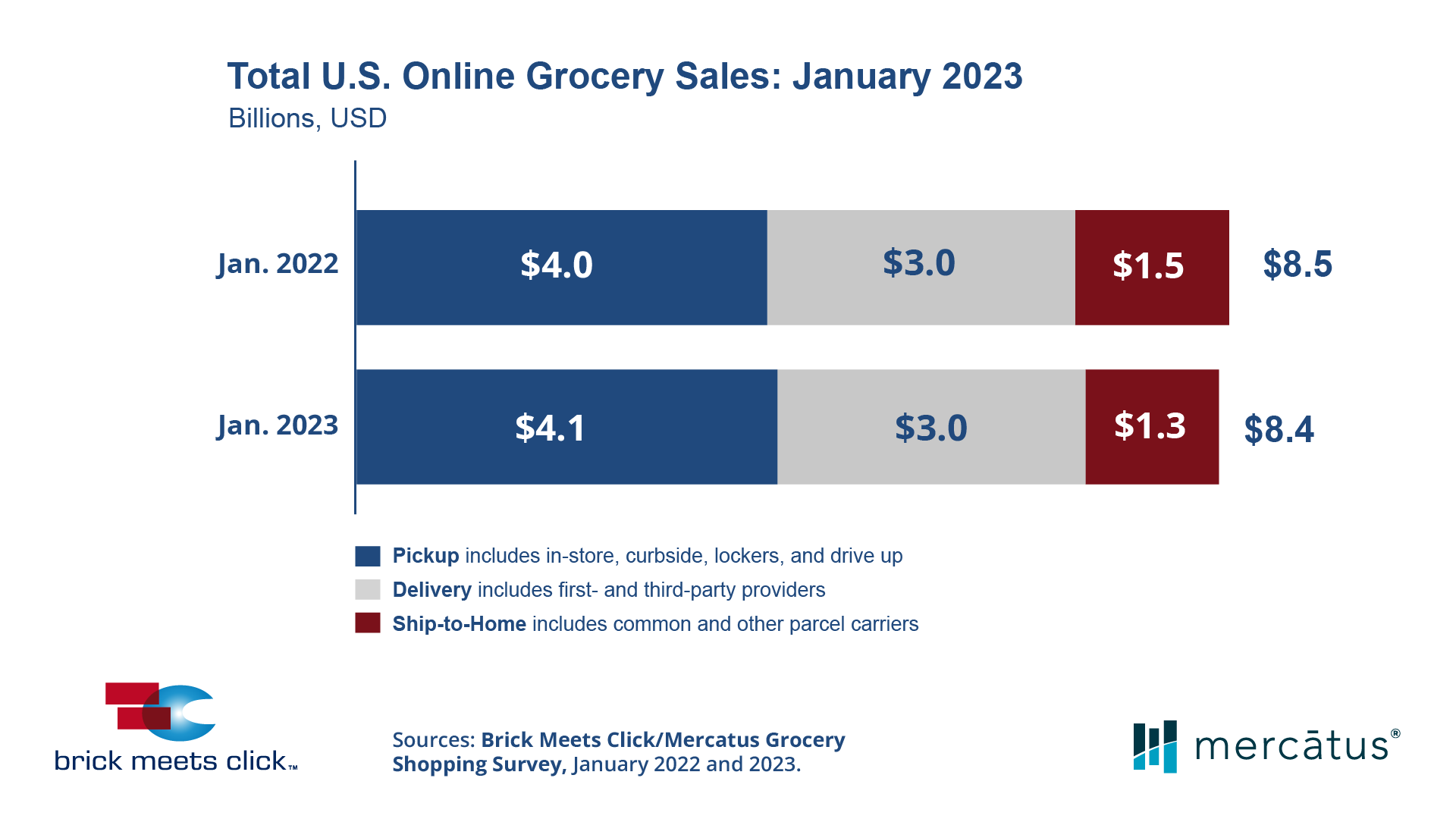

Total domestic e-grocery sales last month were $8.4 billion, down 1.2% from January 2022, and off 7.7% from December, the companies said in their monthly report.

Compared to the previous January, ship-to-home sales were down 15% to $1.3 billion, with store pickup increasing nearly 3% to $4.1 billion. Home delivery, i.e., orders fulfilled from a local grocery retailer vs. a big-box fulfillment center, most often by a third-party service, was up less than 1% to $3 billion.

E-grocery as a whole represented a bit more than 12% of total domestic grocery spending in January, slightly higher than in 2022 and helped by strength overall in the sector, the companies found. At its peak in January 2021, it was at 14.4% of total spend.

In terms of the stickiness of e-grocery buying behavior, it’s still 4.2x what it was pre-pandemic, using August 2019 as the proxy baseline, and at 90% of the January 2021 peak, said David Bishop, a partner with Brick Meets Click.

Among the segments, grocery pickup is 6x vs. the baseline, and delivery nearly 6x, Bishop said. Ship-to-home, the most expensive option for consumers, is still up 1.5x from August of 2019.

“There has been some pullback but off an extremely elevated base compared to before the pandemic,” Bishop said. “Mass adoption exposed a large swath of households to delivery and pickup, which they found as an acceptable alternative to shopping in store. I’m not suggest they completely abandoned shop in store, it just plays a role where it didn’t before, especially for large stock-up shopping trips.”

From January 2021 to last month, ship to home, i.e., boxed e-grocery orders coming from players like Boxed, Costco, Amazon, Walmart, Target, etc., was down almost 40%, Bishop said. During the same period, home delivery was down 6% while store pickup increased 5%.

“It’s not completely surprising,” he said. “A lot of consumers tried delivery and pickup. Back then, we had the subsegment of rapid grocery delivery, concentrated in large metros, and we were in the period of cheap (government) money, which we’re just exhausting now. And there were more services available than there are now.”

Inflation of course has also taken a bite out of grocery delivery, Bishop said, with its fuel surcharges, fees and tips, which pushes more retailers toward pickup.

“While we don’t publish it, mass market retailers like Walmart and Target disproportionally skewed toward pickup vs. conventional grocers that skew toward delivery,” he said. “(Pickup) is a main thrust for how mass players are driving omnichannel, because it’s more aligned with their cost to serve model and provides more control over the experience.”

Asked about Amazon’ recent decision to raise the threshold for free delivery from $35 to $150 on orders from Fresh stores, with a $9.95 delivery fee below that figure, Bishop said it was a welcome acknowledgement of the costs involved and what other grocers are facing. It was also a realization that lower-income Prime members, many enticed through discounted membership at $6.99 per month, weren’t going to spend with Amazon on higher-margin goods.

Amazon’s struggles to make grocery economics work have been well-documented, and the company overall is scaling down in a hurry as it posts red quarters. Still, CEO Andy Jassy wants to find ways to “go big” on the category, he told the Financial Times, even as stores close.

“The cost of delivery could be $8 or $10 per order, regardless of the size,” Bishop said. “So, it was hard for Amazon Fresh to justify free delivery at that level. Amazon may have been very successful in bringing on new members, but they were arbitraging Prime to get the lowest delivery cost out there, and not doing all the things Amazon was hoping they would.”